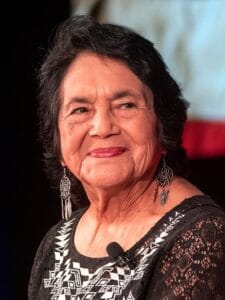

Dolores Huerta

Champion for Her People

Dr. Johnnetta Betsch Cole has long been impressed with the courage and strength of Dolores Huerta. She reflects on a particular role that Delores Huerta’s work with the 1965-1970 Delano Grape Strike and Boycott played in her life and the life of her oldest son, David Kamal Betsch Cole.

During the time that Dolores Huerta was the major organizer among Chicano and Filipino farm workers on the Delano farm, Dr. Cole made sure that her young son, David, was supporting the boycott and strike. So, she taught him that the fruit he loved to eat was called union grapes. And he should not ever eat any other kind.

Dr. Cole also shares that over the years, on every occasion when she has had the great honor of being with the legendary Dolores Huerta, she has been struck by a duality that is so central to who Ms. Huerta is: she is simultaneously so humble and so powerful.

“Si, se puede.” Yes, we can!”

Dolores Huerta

Dolores Huerta is deeply connected to this iconic phrase,”Si se puede” that was first used as a rallying cry for the labor movement. It continues to be a rallying cry for other social justice movements.

Dolores Clara Fernandez Huerta is a deeply respected and beloved Chicana who today, at age 95, remains active in the labor movement, the movement for Chicano rights, the movement for women’s rights and the civil rights movement. Born on April 10, 1930 in Dawson, New Mexico, and raised in Stockton, California, Dolores Huerta was greatly influenced by her parents. Her father Juan Fernandez, was both a miner and farm worker who became a state legislator in 1938. He left the family when Ms. Huerta was three. She and her two brothers were raised primarily by her grandfather, while her mother worked multiple jobs until she bought a restaurant and small hotel. Alicia Fernandez was another early example to Dolores Huerta of community activism for fair treatment of workers.

Dolores Huerta received an associate teaching degree from the University of the Pacific’s Delta College. While she was in school, she married Ralph Head and welcomed two daughters into the world. After a short lived marriage she and Ralph Head divorced. A few years later, she married Ventura Huerta, and had five children. That marriage also did not last. She also had four more children with Richard Chavez.

While she was teaching in an elementary school, Dolores Huerta saw that her students were both hungry and impoverished. She was so outraged by the horrific living conditions of her students and their parents who were farm workers that she left the classroom to take direct action. She committed fully to addressing the plight of farm workers and their families.

Co-founding the Stockton chapter of the Community Service Organization in 1955, Dolores Huerta led drives to increase Hispanic voting and improve economic conditions for Hispanics. She also founded the Agricultural Workers Association. A co-worker introduced Dolores Huerta to activist César Chávez, who was also interested in supporting farm workers.

In 1962, Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez co-founded the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), an organization that later became the United Farm Workers (UFW). Through her brilliant negotiating tactics, groundbreaking labor contracts were signed. And she and Cesar Chavez secured collective bargaining rights for farm workers.

Dolores Huerta mobilized the Delano grape strike of 1965 as she rallied workers and organized consumer boycotts across the country to pressure growers. She advocated for safer working conditions and the elimination of deadly pesticides. She championed benefits for workers including unemployment and healthcare. Constantly shouting the powerful slogan she is known for: “Si, se puede,” Dolores Huerta woke up the rest of the country and garnered support across the nation for farm workers.

Despite facing gender discrimination, including from activists, Ms. Huerta became a leading figure in the Chicano movement and the movement for women’s rights as she elevated the voices of Latinas and working-class women. Indeed, because of her social justice work, Dolores Huerta is a shero for all generations of activists.

Throughout the 1970’s and 80’s, Dolores Huerta lobbied the government to improve workers’ legislative representation. Sadly, she was brutally beaten by police at a peaceful protest in 1988. Ms. Huerta then redirected her focus towards political education and community organizing. In the 1990s and 2000’s, she worked tirelessly to elect more Latinos and women from all communities to political office.

In 2002, she established the Dolores Huerta Foundation which trains grassroots organizers and empowers people in marginalized communities.

This non-profit organization is dedicated to inspiring communities to pursue social justice, focused on education equity, civic engagement, LGBTQIA+ equity, and health and safety. The foundation empowers people to implement community-driven solutions towards equality.

While Cesar Chavez was frequently honored during his lifetime, Dolores Huerta did not receive national recognition for decades. It was in 1998 that Ms. Huerta received the Eleanor Roosevelt Human Rights Award, and in 2012, President Obama awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

With grace, courage and humility, Dolores Huerta has been a true changemaker all of her life. Not content to sit by and watch children and families be mistreated, she took action and made a huge impact on farm workers, women and children throughout the United States.

With her hard work and dedication, Dolores Huerta advocates for:

- Humane treatment of farm workers and their families

- Education equity

- Civic engagement

- Civil rights

- Women’s rights

- LGBTQIA+ equity

Lessons from Dolores Huerta’s Life:

Resilience when facing adversity both personally and professionally.

She had 11 children while maintaining a grueling schedule as a full-time organizer. That meant frequent absences from home. She dealt with significant gender discrimination and persisted in lobbying for her people. And throughout it all, she maintained positivity. “I think the importance of doing activist work is to engage people and give them hope. Hope for a better world, hope for a better tomorrow.”

Grassroots organizations can bring about systemic change. Her life illustrates the need to mobilize communities to dismantle entrenched power structures. She has said, “We can’t build a just society without first empowering people to participate in it.”

Intersectional advocacy is critical to social justice. In addition to advocating for humane treatment of farm workers, Dolores Huerta used the power of her voice to focus on women’s rights, immigration reform, reproductive freedom and more. She collaborated with Gloria Steinem to support women and to spotlight sexism within the labor movement. Ms. Huerta is a mighty champion for many marginalized communities.“Every moment is an organizing opportunity, every person a potential activist, every minute a chance to change the world.”

Action Steps You Can Take:

• Spend some time reading about the history of the farm worker’s movement. And based on what you find, ask yourself what role you can play today in supporting that movement.

• Become informed about state and federal legislation about farm workers, and think about what you want to do in response to that legislation.

• Food scarcity is still a big issue for impoverished children in the United States. Consider what you can do to address this issue. An example might be buying something extra when you visit the grocery store to donate to food banks.

Did this article inspire you?

Please share your feedback and share it with others here: